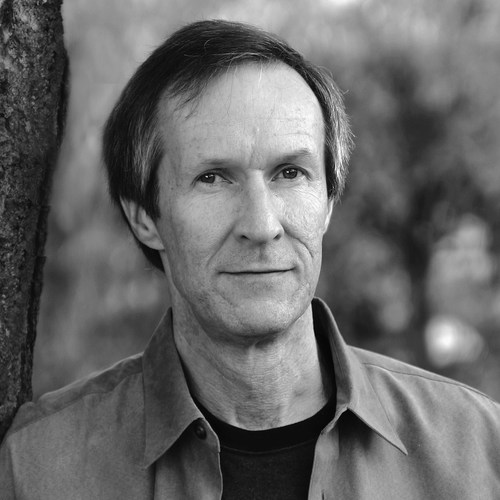

Bogira is originally from the south side of Chicago and he graduated from Northwestern University. He worked briefly for the Chicago Tribune, before moving to the Chicago Reader. Bogira sites more freedom to write about what he wants to and in greater detail as his reasons for the move.

Bogira is the race and poverty beat writer for the "Reader."He also authored the book "Courtroom 302."

"I write about stories involving parts of the city that don't get enough attention," Bogira said.

Urban poverty is one of Bogira's main interests, especially reporting on mental and physical health, as well as criminal justice in those societies.

Bogira has covered a wide variety of stories within those topics. He likes to bring attention to the lesser known news stories that exist in these societies.

For example in the late 1980s, in a high-rise apartment building, one of the most dangerous at the time, on the south side of Chicago, a woman was killed by thieves who entered her home through her medicine cabinet. Bogira wrote the article about diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic, Ruthie McCoy's death.

To effectively report for his 5,000-plus word feature stories, Bogira speaks with family members of the subject of the story, neighbors, mentors, medical experts. Often, he relies on court transcripts, police reports and details from the lawyers in a case.

A major issue that journalists must consider, Bogira said, is the level of access they will have to the various elements, details and sources involved in the story. That is something writers have to consider, especially for longer projects, Bogira said.

Bogira's structure is unique, especially within his longer stories, because they do not always develop in a chronological manner, they skip from flashbacks to flashforwards or the present.

He doesn't write his articles from beginning to end during the writing process. Instead he focusses mostly on the lede and the end of a story first; the middle comes last.

Another element critical when reporting a story is skepticism. A reporter must double-check every fact and detail to avoid errors.

"If your mom says she loves you, check it out," Bogira said about the level of skepticism.

If a writer is unsure of the validity of someone's statement, be sure to attribute the statement to that person.

Bogira now spends four to six weeks on any given feature story, which usually hits the 5,000 word count. He used to spend three months on a story and that story would be eight to ten thousand words.

"People are eager to talk, especially to those who don't often get listened to," Bogira said.

Beat reporting is also unique because the reporter learns in greater depth what they are writing about, since they are focussed on one environment regularly.

Bogira recommends paying attention to every little thing when reporting a story to get the little details that make a story more memorable.

Bogira still keeps in touch with several of the people he's written about, including

"We're 'just presenting facts,' but really we're a guide to the reader in certain directions," Bogira said. "I start with the background then explain the solo crime to empathize."

Follow Steve on Twitter: @stevebogira

By Emily Brown